Reviews of the literature: types and distinctions

Literature reviews are important for exploring existing knowledge, evaluating the evidence base and identifying areas of limited understanding which may require further investigation.

Literature reviews vary depending on the purpose for which they are being produced. An undergraduate, for example, may be expected to write a literature review for an assignment or dissertation. The type of literature review employed here is likely to differ from that produced by a postgraduate conducting a broader review for a PhD or a journal article, or by a researcher for a large-scale research project.

A magnifying glass and glasses on a book in a library.

Let’s take a look at some of the different types of literature review…

What types of literature reviews are there?

There are many different types of literature reviews which differ in terms of aims, scope, level of rigour and analysis. These include systematic reviews, scoping reviews, critical reviews, quantitative or qualitative meta-analysis reviews, rapid evidence reviews and traditional literature reviews, among many others (see Grant and Booth, 2009 for further details).

For the purposes of this blog, I am going to focus on some of the most common types of reviews:

Narrative/Traditional reviews

Systematic reviews

Scoping reviews

Rapid Evidence Assessments (REAs)

Narrative/Traditional reviews

The narrative or traditional literature review provides an overview and critical evaluation of the literature on a specific topic, identifying, summarising and synthesising current knowledge, whilst also establishing gaps in understanding.

This type of review tends towards a more qualitative interpretation of existing knowledge and is valuable for highlighting potential avenues for further research and refining research questions. As Paré and Kitsiou (2017) note, however, within this unsystematic approach, information selection is subjective and inclusion criteria are not made explicit. The lack of transparency in this method is therefore often cited as a criticism, as well as the potential for bias.

This type of method is more commonly used by undergraduates and is often presented as a chapter within a dissertation to demonstrate how the study fits into the existing field of research, rather than in policy and practice where more rigorous and systematic approaches to evidence review are sought.

Systematic Reviews

At the other end of the scale are systematic reviews which involve the collation of empirical evidence on a particular issue, using specific methods to enhance reliability. They use pre-determined eligibility criteria (inclusion and exclusion), seek to identify all research (published and unpublished) which meets the criteria, and often involve multiple reviewers. The findings of the studies are then assessed and synthesised. Systematic reviews are therefore distinguishable from traditional literature reviews as they are more comprehensive, systematic, rigorous and transparent, thus enhancing the reliability and validity of the findings.

Victor (2008: 3) highlights the key stages of the systematic review as involving: “the definition of the review scope, questions and protocol; the search for and selection of evidence; quality appraisal of evidence and the review process; data extraction and synthesis; and reporting and dissemination”.

Defining the review scope, questions and protocol requires the inclusion of a detailed description of the planned methods. According to Collins et al. (2015: 15), protocols should include: authors, background, objective, scope, conceptual model, methods, search keywords, a strategy for type of evidence used, inclusion and exclusion criteria, strategy for extracting information, strategy for critical appraisal, plan for synthesis, outline of conflicts of interest, references and a timeline for the review.

The search for and selection of evidence includes deciding on types of evidence and careful selection of search terms. Multiple databases will be searched and will include published and unpublished literature, before the screening of titles and abstracts, and then reading full texts.

Quality appraisal of evidence and the review process is necessary to assess the quality of conclusions and to check individual assessments of the evidence through the use of two or more reviewers. Using a minimum of two reviewers ensures the quality and reliability of the findings.

Data extraction and synthesis involve documenting details such as methods, samples, analysis and findings, usually in a template table or chart, before assessing commonalities and differences within the data.

Reporting and dissemination are the final stage and tend to include the production of a document which includes an introduction, methodological protocol and detailed methodological appendices, nature of evidence, findings, conclusions and recommendations.

Systematic reviews benefit from the inclusion of a wide range of studies and types of material (Grant and Booth, 2009), as well as a more rigorous approach leading to greater reliability and validity of the findings. They are considerably time intensive, however, as well as resource-heavy (Victor, 2008).

Due to their rigour and systematic approach, systematic reviews tend to be used to inform evidence-based decisions within policy-making and research, especially within healthcare.

Scoping reviews

Scoping reviews, as their name suggests, identify the scope of literature on a specific topic, in terms of the nature and size of the literature, to assist in determining gaps in knowledge or assess the need for a more systematic review (Kitsiou, 2017). They tend to take a broad approach to reviewing the literature, with less focus on a defined research question than systematic reviews. They can be as time-intensive as systematic reviews, but quick scoping reviews are often used, which take considerably less time.

Scoping reviews are especially useful for investigating the evidence base within developing research areas (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005). Limitations arise in relation to rigour, however, which increases the risk of bias (Grant and Booth, 2009).

Scoping reviews are most commonly used for synthesising evidence, particularly in the healthcare sector, and can be used for this purpose in their own right. They can also be used as a predecessor to a more thorough systematic review (see Munn et al., 2018).

Rapid Evidence Assessments (REAs)

Rapid Evidence Reviews (REAs) are more rigorous than a literature review and scoping review but not as thorough as a systematic review. They involve the use of systematic methods in order to provide as rigorous a review as possible but may require the omission of a particular stage of the systematic review in order to shorten the timeframe in which they are conducted. Different techniques can be used here, as Grant and Booth (2009: 100) explain, such as:

…carefully focusing the question, using broader or less sophisticated search strategies, conducting a review of reviews, restricting the amount of grey literature, extracting only key variables and performing only ‘simple’ quality appraisal. The reviewer chooses which stages to limit and then explicitly reports the likely effect of such a method.

REAs are valuable for identifying the range and quality of evidence on an issue and knowledge gaps. Due to restrictions used to reduce the timescale, however, there is an increased risk of bias, although ensuring explicit documentation of methodology can help to reduce this (Grant and Booth, 2009).

As REAs offer rigour and a systematic approach within a reduced timescale, they are frequently used for policy and practice.

What are the key distinctions between the different types of reviews?

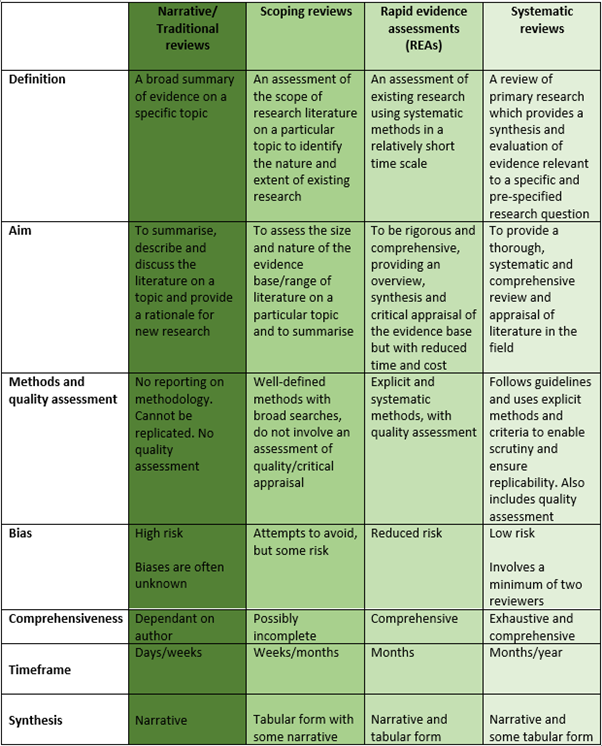

Whilst variation exists in relation to definitions and features of the different forms of review, the table below collates some of the most commonly-cited key details, features and characteristics of different types of reviews to underline the main differences between them.

A table in green colours with text showing the differences between types of literature review.

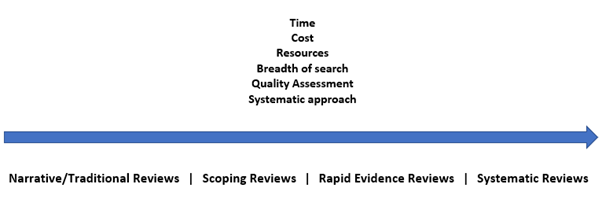

White background with black text: “time, cost, resources, breadth of search, quality assessment, systematic approach” above a long blue arrow.

How do I choose the right kind of review?

The type of review you use will depend on the purpose for which the review is being conducted, and the time and resources available. Are you trying to identify a gap, assess existing research in a field, or evaluate the size and scope of current knowledge? Your answers here will help you to determine the right kind of review for you.

I need more information. Where can I look?

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32.

Booth, A., Papaioannou, D. and Sutton, A. (2016) Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. 2nd Edition. London: Sage.

Collins, A., Coughlin, D., Miller, J. and Kirk, S. (2015) The Production of Quick Scoping Reviews and Rapid Evidence Assessments: A how to guide. Joint Water Evidence Group.

Grant, M.J. and Booth, A. (2009) ‘A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies’. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26: 91-108.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H. & O'Brien, K.K. (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69.

Munn, Z., Peters, M.D.J., Stern, C. et al. (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143.

Paré, G. and Kitsiou, S. (2017) Methods for Literature Reviews. In: F. Lau and C. Kuziemsky (eds) Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria.

Victor, L. (2008) Systematic reviewing. Social Research Update. Issue 54. http://www.sco.surrey.ac.uk/sru/

Blog image from: <a href='https://www.freepik.com/photos/book-publishing'>Book publishing photo created by jcomp - www.freepik.com</a>